10/31/2025

Feeding Smarter

Jack Bobo

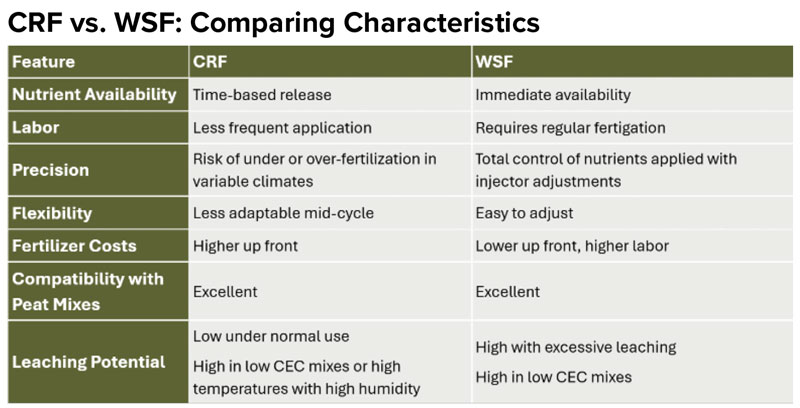

Fertilizer strategies remain at the core of successful greenhouse and nursery production. Growers are constantly balancing efficiency, cost, plant performance and sustainability when deciding how to deliver nutrients. Two dominant approaches each bring distinct advantages and limitations: controlled-release fertilizers (CRFs) and water-soluble fertilizers (WSFs). Understanding their differences, as well as how they interact with substrates, crop cycles and management practices, allows growers to maximize fertilizer efficiency while improving plant growth.

Fertilizer fundamentals

Fertilizers are manufactured in a variety of forms (powders, crystals, granules or coated prills) and may be organic or inorganic. They can supply single nutrients, blends of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium (NPK), and micronutrients, often stabilized with carriers or anti-caking agents. Some dissolve instantly in water, while others are engineered for gradual release. They may be:

- Blended into substrates (as a starter charge or CRF incorporation)

- Dissolved in irrigation water (fertigation or foliar sprays)

- Top-dressed onto the growing medium

One key factor to monitor is pH impact. Ammonium-based fertilizers tend to lower substrate pH, while nitrate-based fertilizers raise it. Water alkalinity also plays a significant role: high alkalinity water buffers and pushes pH upward over time, whereas low alkalinity water provides no buffering. This makes testing source water essential before choosing a fertilizer program.

Controlled-release fertilizers (CRFs)

Controlled-release fertilizers (CRFs) are water-soluble nutrients encapsulated in a semi-permeable polymer coating. When moisture penetrates this polymer capsule, it dissolves the fertilizer inside, which then diffuses slowly through microscopic pores in the coating. The capsule eventually empties, leaving behind only the shell. The release rate of CRFs is influenced by environmental factors like temperature and moisture, as well as by brand and coating characteristics.

CRFs are particularly popular in outdoor, low-touch, long-cycle crops where growers want reduced labor and consistent feeding. For best results, it’s important to match the product to crop duration, monitor water and substrate pH, maintain proper greenhouse temperatures, and watch for signs of nutrient imbalance. Potting mixes with CRF blended into them should be used promptly, as prolonged storage (especially under high temperature or humid conditions) can compromise coating integrity and cause early nutrient release, leading to elevated EC.

Water-soluble fertilizers (WSFs)

Water-soluble fertilizers (WSFs), sometimes referred to as constant liquid feed, are the opposite of CRFs in terms of nutrient availability. Because they dissolve completely in irrigation water, WSFs provide immediate access to nutrients throughout the root zone. This makes them ideal for precision fertigation in both short- and long-cycle crops. With WSFs, growers can:

- Adjust formulations as crops progress

- Switch between acidic and basic fertilizers depending on water and crop needs

- Apply custom blends or create on-site mixes tailored to their operation

The main challenge of WSFs lies in management: complex systems, stock tank monitoring, injector calibration and water quality all demand frequent attention. Staff must be properly trained on monitoring, stock tank preparation and safety precautions. Growers should adjust concentrations based on seasons and growth stages, maintain a leaching fraction to prevent salt buildup, and check pH and electrical conductivity weekly.

Substrate interactions

The effectiveness of fertilizers is also shaped by the growing substrate. Substrate components vary in their cation exchange capacity (CEC); this is their ability to retain and release nutrients on a chemical level.

- Peat moss and vermiculite provide high CEC, holding nutrients effectively

- Bark and coir fall in the medium range

- Perlite and wood fiber have little to no CEC, meaning nutrients leach easily

- Compost provides high CEC and introduces beneficial biological activity that can influence nutrient dynamics (in a positive way in organic production), therefore some precautions should be taken.

When using low-CEC substrate components like wood fiber in high amounts, the risk of nutrient loss is higher, making fertilizer choice critical. However, the combination of peat and wood fiber will actually see an increase in nutrient-holding capacity. Beyond CEC, factors like water retention and air space in the root zone also influence nutrient availability. For example, combining wood fiber with peat can improve the root zone environment and enhance nutrient retention, especially in nutrient-rich fertigation systems. This increases the overall nutrient holding capacity of a substrate despite wood fiber’s low CEC.

Wood fiber also introduces unique nutrient dynamics due to its high carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio. Microbial activity in wood fiber-rich mixes tends to immobilize nitrogen, effectively “stealing” it from the root zone. Using very high percentages of wood fiber in a substrate can undermine fertilizer performance and create unexpected deficiencies. If growers try to compensate by adding large quantities of CRFs, the result may be salt accumulation, which stresses roots and reduces water uptake. Understanding substrate dynamics is key when choosing a feeding strategy.

Cost considerations

When evaluating cost efficiency between CRFs and WSFs, growers must consider several factors. CRFs have higher upfront costs but save on labor and require minimal infrastructure. In contrast, WSFs demand daily monitoring, injection systems and more equipment, but offer greater nutrient use efficiency when well managed. Climate variability also plays a role—CRFs carry more risk in unpredictable conditions, while WSFs allow for real-time adjustments. Ultimately, CRFs tend to be more efficient for long-term, low-maintenance crops, whereas WSFs are better suited for high-value crops in precision greenhouse environments.

Baseline and fine-tuning: Why hybrid feeding works well

Incorporating CRFs at planting provides a steady, low-level nutrient supply that keeps crops fed consistently, even during interruptions in fertigation schedules. This “nutrient insurance” reduces the risk of deficiencies during critical growth phases. Because CRFs cannot be adjusted once applied, a combined approach with WSFs allows growers to respond dynamically to crop signals. Whenever plants show signs of nutrient stress, seasonal shifts demand different formulations, or market pressures require rapid growth finishing, WSFs allow precise and immediate intervention. Hybrid approaches are increasingly favored in commercial greenhouses because they offer the best of both worlds: the reduced labor and consistency of CRFs paired with the flexibility and responsiveness of WSFs.

Conclusion

Feeding smarter means selecting the right fertilizer strategy for each operation. CRFs excel in long-term, low-labor applications but are vulnerable to environmental variability. WSFs deliver unmatched precision and flexibility but require significant management and infrastructure. The most efficient systems can combine both, leveraging CRF for a steady baseline and WSF for adaptive, responsive feeding.

Ultimately, successful fertility management depends on understanding substrates, crop cycles and local water conditions. By embracing best practices and monitoring closely, growers can optimize plant health, reduce waste and improve profitability. Our team of grower advisors is available to support decision-making by helping you evaluate your fertilizer options, interpret crop responses and align practices with production goals. Contact us to learn how our expertise can complement your operation. IG

Jack Bobo is an R&D Grower Advisor with Berger with a deep-rooted passion for agriculture and sustainable production. With a background in horticulture and a Ph.D. from NC State focused on wood-based substrates, Jack combines hands-on research with grower collaboration to drive innovation in greenhouse production. His career reflects a lifelong commitment to advancing science-based growing solutions.